Making Waves

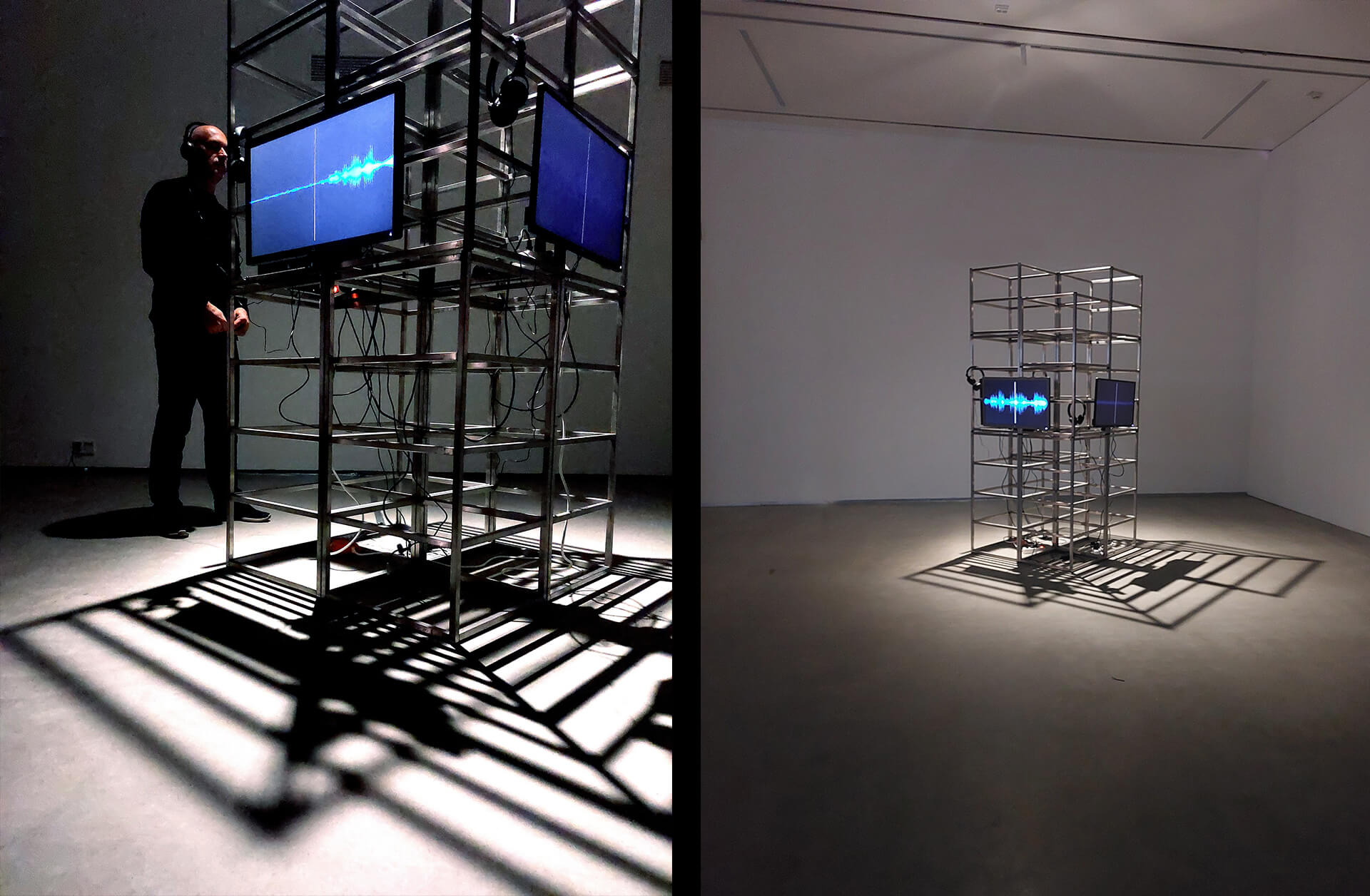

Porvoon Taidehalli, Finland, 2022

Sound research: Klitsa Antoniou

Sound Composition: Demetris Savva

Technological Design and Production: George Lazoglou

Making Waves

Klitsa Antoniou’s work, always drawing from archival material, delves into issues of space, confinement, personal and political borders, and censorship in order to provide an immersive, empathic, multisensorial and participatory experience. By concentrating on incarcerated spaces, the artist brings these heterotopic spaces to the Porvoo Art Hall to release their imaginative potential within the space of the gallery and its rich history. These transgressive acts of transculturation aim to light up an imaginary spatial field, a set of relations that are not separate from dominant structures and ideology but go against the grain and offer lines of flight and as Michel Foucault puts it, a ‘passage which is an enclosure’. (Foucault 1987, 76). These passages offer a route to the outside, thus detaching the viewers from themselves to generate the possibility of emotional empathic identification with the political acts and personal suffering of people like Rosa Luxemburg and other incarcerated political prisoners and people who flee conflict zones and economic depravations, to bring these to the present precarious times we live in.

The multimedia exhibition uses sound, video and found material to marry the concept with the materiality of the installations. The video installation Something Exceedingly Strange is Happening this Year (2020) brings the visitor close to Luxemburg’s writings with a video projection which uses her prison letters and diaries. The juxtaposition of the reading of her writings and the mesmerising visuality of the video installation attempt an empathic identification with Luxemburg’s fears, pain but most importantly, imaginative optimism. Recordings of illegal and pirate stations in the installation Making Waves (2022) raise issues of political and personal censorship in an era of constant surveillance where the panopticon of the state has expanded its web to unprecedented dimensions. Freedom of movement, surveillance and the artificiality of borders is explored in the installation No Photographs Should be Taken Beyond this Point (2020) and pose pertinent questions in relation not only to zones of armed conflict but, most importantly, to our everyday lives and the borders that are erected around us.

Something Exceedingly Strange is Happening this Year (Video Installation, 2020), uses the narration of Rosa Luxemburg’s prison letters and the mesmerising visuality of the video projection in an attempt to create affective empathy, inasmuch as it proposes to alert the viewer to Luxemburg’s emotions – her fear, her pain but also, importantly, her unyielding optimism.

Heterotopias, like prisons, are not formations of unusual juxtapositions but they produce an impossible or unthinkable space that could only take place in language. This is the imaginary world of works of art, a space where the disorder of the imagination reveals the fragments of possible orders that splinter the familiar. The sound and visuality of the video installation provide the space for the visitor to enter this imaginary world and imagine possible orders that challenge the familiar and most importantly, to enable the visitor to the exhibition to enter the world of ‘bruises’ of Rosa Luxemburg and the ‘courage of a new life’.

For Luxemburg, a Jewish woman, un-belonging was strength. It must surely have played its part in helping her to soar mentally beyond the walls of the prisons where she often found herself, as her writings – her letters, pamphlets, journalism, political tracts – so amply testify. ‘The fire of her heart melted the locks and bolts and her iron will tore down the walls of the dungeon,’ wrote her close friend, the socialist feminist Clara Zetkin, ‘[gathering] the amplitude of the coursing world outside into the narrowness of her gloomy cell.’ In whatever conditions she found herself – in Warsaw, she was one of fourteen political prisoners crammed into a single cell – Luxemburg never lost her fervour, her joy as she put it, amidst the horrors of the world. ‘My inner mood’, she wrote after listing the indignities of her captivity, ‘is, as always, superb’ and ‘see that you remain a human being,’ she wrote to Mathilde Wurm from Wronke prison in December 1916: ‘To be a human being is the main thing above all else.’ We could learn a lot in our present state of affairs from this short but highly poignant sentence. ‘Enthusiasm combined with critical thought,’ Luxemburg proclaimed in one of her very last letters, ‘what more could we want of ourselves!’ It is exactly the importance of critical thought that is under fire in our world one hundred years after Luxemburg wrote this.

Freud used the mystic or magical writing pad to describe the psyche as a set of infinite traces. The mind is its own palimpsest. It cannot be held down to a single place. The mind of Rosa Luxemburg could travel outside the confines of the sell to imaginary gardens and finally to the space of the gallery and the visitor to the exhibition, bringing with her humanity, humility, enthusiasm, and critical thinking, and last but not least, the fire of her heart.

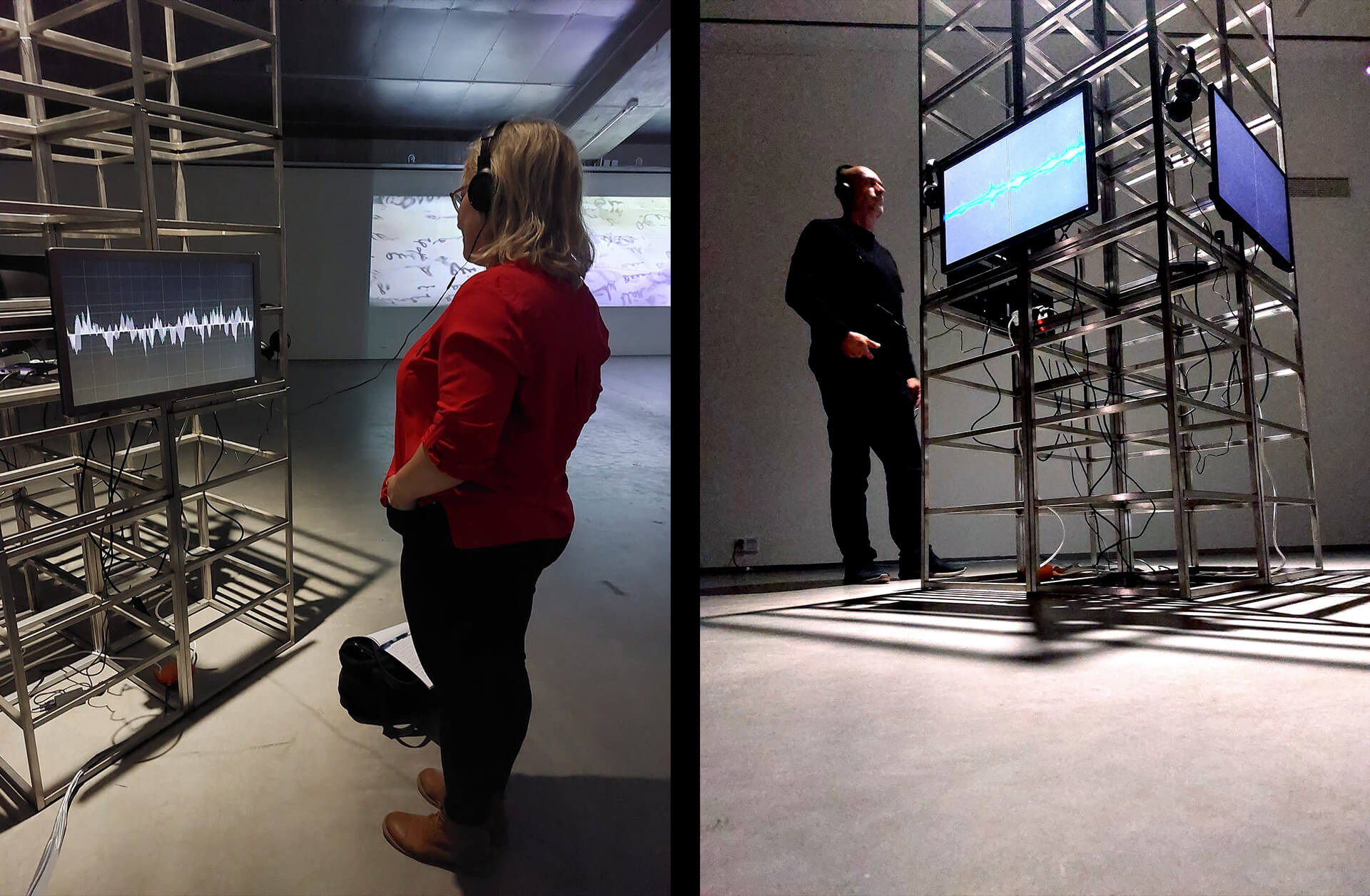

Making Waves (multimedia installation, 2022), transforms the exhibition space into a ‘muted’ acoustic space. The three video screens bring to the visitor the image of sound, but the visitor has the choice to listen to the sound via the headphones. The sound is taken from broadcast recordings of illegal and pirate stations, raising issues of political and personal censorship in an era of constant surveillance where the panopticon of the state has woven a mighty web of intricate entanglements. As in the case of the original broadcasts, when the individual had the option to tune in to these stations, so too in the space of the gallery visitors may choose to listen to these broadcasts or not.

Censorship is a strong word. The mere act of uttering the word calls to mind pictures of totalitarian regimes, or narrow-minded bureaucrats supressing content they find offensive according to prudish criteria. It is also a word which in its popular perception corresponds to the ‘either/or’ modality. A work of art is either supressed or not. Yet, as contemporary debates over the definition of the term have shown, censorship can occur outside of this black and white binary, in less aggressive and less traceable ways, even in liberal democratic societies. As Judith Butler noted, censorship ‘as a productive form of power, may work in implicit and inadvertent ways’ (1998, p.249). The installation problematises censorship, freedom of speech and artistic expression.

Like in the case of the heterotopic space of the prison from where Rosa Luxemburg wrote her letters, these broadcasts were made from pirate stations often based in another heterotopic space, the ship, which were moored in the open sea in international waters to avoid being confined by national censorship laws, thus exposing the artificiality of borders which is the theme of the last installation.

No Photographs should be taken beyond this point (Multimedia installation, 2020), uproots from their original political context the found signs to display them in the gallery: the armed conflict in Cyprus that led to the division of the island in 1974 and the creation of a border that divides the island from East to West which is known in Cyprus as the Green Line. A buffer zone runs along the Green Line and the signs that the artist uses can be found all along the length of the border. The two signs that are placed in the gallery alert passers-by in a multilingual, and prohibitively performative language, of the restrictions that the border imposes to free movement; but they also prohibit the visual capture of the border lands. However, the artist inverts this prohibition by inserting cameras in the signs, therefore transgressing the prohibitive nature of the sign but also bringing to the gallery space questions around surveillance in our digital age. What becomes more questionable with the artistic intervention is the artificiality and absurdity of borders in a time when the borders of Europe seem to be under threat. (Dr Gabriel Koureas, 2022)

Supported by

Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Helsinki, Finland

Cyprus Deputy Ministry of Culture

Cyprus University of Technology

Cut Contemporary Fine Arts Lab